Jeux de coloriage¶

Le notebook explore quelques problèmes de géométrie dans un carré.

[1]:

%matplotlib inline

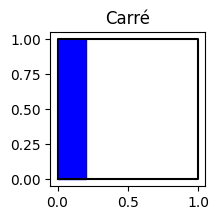

Colorier un carré à proportion¶

On souhaite colorier 20% d’un carré. Facile !

[2]:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.patches as pch

def carre(ax=None):

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(2, 2))

ax.plot([0, 0, 1, 1, 0], [0, 1, 1, 0, 0], "k-")

ax.set_title("Carré")

return ax

ax = carre()

ax.add_patch(pch.Rectangle((0, 0), 0.2, 1, color="blue"));

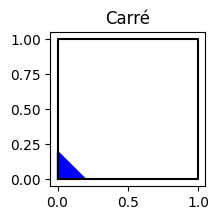

Colorier en diagonale¶

[3]:

import numpy

ax = carre()

ax.add_patch(

pch.Polygon(numpy.array([(0, 0), (0.2, 0), (0, 0.2), (0, 0)]), color="blue")

);

Moins facile…

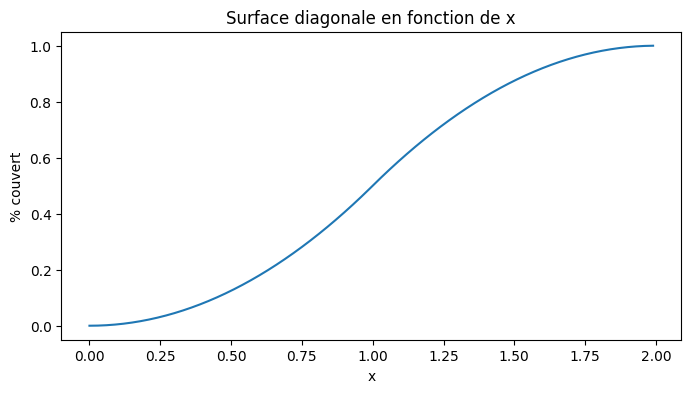

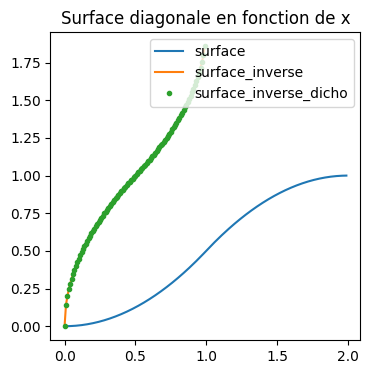

Fonction de la surface couverte¶

[4]:

def surface(x):

if x <= 1.0:

return x**2 / 2

if x <= 2.0:

return surface(1) + 0.5 - surface(2 - x)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(8, 4))

X = numpy.arange(0, 200) / 100

Y = [surface(x) for x in X]

ax.plot(X, Y)

ax.set_title("Surface diagonale en fonction de x")

ax.set_xlabel("x")

ax.set_ylabel("% couvert");

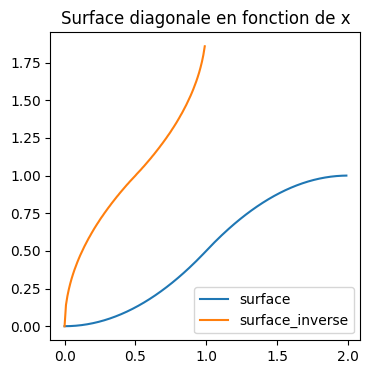

Ce qui nous intéresse en fait, c’est la réciproque de la fonction. Première version, sans savoir calculer mais en supposant qu’elle est croissante.

[5]:

def surface_inverse(y, precision=1e-3):

x = 0

while x <= 2:

s = surface(x)

if s >= y:

break

x += precision

return x - precision / 2

surface_inverse(0.2)

[5]:

0.6325000000000005

[6]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(4, 4))

X = numpy.arange(0, 200) / 100

Y = [surface(x) for x in X]

ax.plot(X, Y, label="surface")

X2 = numpy.arange(0, 100) / 100

Y2 = [surface_inverse(x) for x in X2]

ax.plot(X2, Y2, label="surface_inverse")

ax.set_title("Surface diagonale en fonction de x")

ax.legend();

Ca marche mais…

[7]:

%timeit surface(0.6)

139 ns ± 3.21 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10,000,000 loops each)

[8]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inverse(y)

120 µs ± 10.3 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10,000 loops each)

Et c’est de plus en plus long.

[9]:

%timeit surface_inverse(y * 2)

197 µs ± 53.6 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1,000 loops each)

Il y a plus court.

[10]:

def surface_inverse_dicho(y, a=0.0, b=2.0, precision=1e-3):

while abs(a - b) >= precision:

m = (a + b) / 2.0

s = surface(m)

if s >= y:

b = m

else:

a = m

return (a + b) / 2.0

surface_inverse_dicho(0.2)

[10]:

0.63232421875

[11]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(4, 4))

X = numpy.arange(0, 200) / 100

Y = [surface(x) for x in X]

ax.plot(X, Y, label="surface")

X2 = numpy.arange(0, 100) / 100

Y2 = [surface_inverse(x) for x in X2]

ax.plot(X2, Y2, label="surface_inverse")

X3 = numpy.arange(0, 100) / 100

Y3 = [surface_inverse_dicho(x) for x in X2]

ax.plot(X2, Y2, ".", label="surface_inverse_dicho")

ax.set_title("Surface diagonale en fonction de x")

ax.legend();

Ca marche.

[12]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inverse_dicho(y)

2.9 µs ± 280 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100,000 loops each)

[13]:

%timeit surface_inverse_dicho(y * 2)

3.74 µs ± 252 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100,000 loops each)

Près de 50 fois plus rapide et cela ne dépend pas de y cette fois-ci. Peut-on faire mieux ? On peut tabuler.

[14]:

N = 100

table = {int(surface(x * 1.0 / N) * N): x * 1.0 / N for x in range(0, N + 1)}

def surface_inv_table(y, N=N, precision=1e-3):

i = int(y * N)

a = table[i - 1]

b = table[i + 1]

return surface_inverse_dicho(y, a, b, precision=precision)

surface_inv_table(0.2)

[14]:

0.63234375

[15]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inv_table(y)

2.03 µs ± 221 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100,000 loops each)

[16]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inv_table(y * 2)

1.62 µs ± 30.7 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100,000 loops each)

C’est mieux mais cette solution est un peu défectueuse en l’état, trouverez-vous pourquoi ? L’expression len(table) devrait vous y aider.

[17]:

len(table)

[17]:

51

Version mathématique¶

Pour cette fonction, on sait calculer la réciproque de façon exacte.

[18]:

def surface(x):

if x <= 1.0:

return x**2 / 2

if x <= 2.0:

return surface(1) + 0.5 - surface(2 - x)

def surface_inv_math(y):

if y <= 0.5:

# y = x**2 / 2

return (y * 2) ** 0.5

else:

# y = 1 - (2-x)**2 / 2

return 2 - ((1 - y) * 2) ** 0.5

surface_inv_math(0.2), surface_inv_math(0.8)

[18]:

(0.6324555320336759, 1.3675444679663242)

[19]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inv_math(y)

152 ns ± 11.1 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10,000,000 loops each)

[20]:

y = surface(0.6)

%timeit surface_inv_math(y * 2)

163 ns ± 13.2 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10,000,000 loops each)

Il n’y a pas plus rapide mais cette option n’est pas toujours possible. Je passe la version écrite en C++, hors sujet pour le moment.

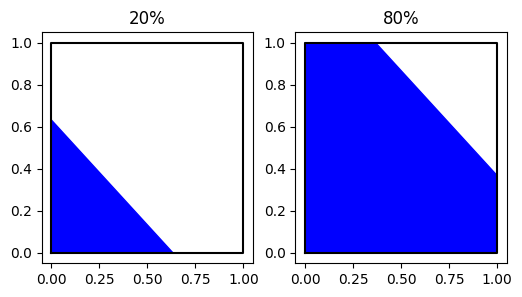

Retour au coloriage¶

[21]:

def coloriage_diagonale(y, ax=None):

ax = carre(ax)

if y <= 0.5:

x = surface_inv_math(y)

ax.add_patch(

pch.Polygon(numpy.array([(0, 0), (x, 0), (0, x), (0, 0)]), color="blue")

)

else:

ax.add_patch(

pch.Polygon(numpy.array([(0, 0), (1, 0), (0, 1), (0, 0)]), color="blue")

)

x = surface_inv_math(y) - 1

ax.add_patch(

pch.Polygon(numpy.array([(1, 0), (1, x), (x, 1), (0, 1)]), color="blue")

)

return ax

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(6, 3))

coloriage_diagonale(0.2, ax=ax[0])

coloriage_diagonale(0.8, ax=ax[1])

ax[0].set_title("20%")

ax[1].set_title("80%");

A quoi ça sert ?¶

Une programme est la concrétisation d’une idée et il y a souvent un compromis entre le temps passé à la réaliser et la performance qu’on souhaite obtenir. Et c’est souvent sans fin car les machines évoluent rapidement ces temps-ci.

[ ]: